|

What seemed like three very short weeks in Utah, I am having time to reflect on what was absolutely the most amazing time in my life. This experience was by far one of the most challenging and rewarding experiences I have ever had the privilege of which to be a part. Academically, professionally, and socially, this program totally exceeded my expectations. Looking back during my time in Utah, starting with the opening dinner we had at the Arts Building, we were completely and totally treated with the utmost respect and professionalism, yet we already felt that we were all friends. At no time did I ever feel like I was uncomfortable or like I couldn’t be myself. There was an extreme amount of reading to do for this workshop, not gonna lie, but for English people, we are used to that, and it wasn’t something that we weren’t already prepared for. I was totally exhausted, it was extremely hot, and I constantly could have napped at any given second, and I loved every minute of it. I felt challenged, I felt pushed, and extremely limited on time, and I wouldn’t have wanted it any other way. Our schedule felt overloaded, but we were like sponges, taking in more and more and absorbing every ounce of information that we could. The speakers, the readings, the presentations, the trips, the plays, the lessons, the absolute wealth of information from the instructors was absolutely overwhelming. I cannot say enough about the multitude of information at our fingertips that I would never in a million years be able to gain in any other situation. I cannot even begin to speak about the emotional and social connections that were made on this trip. From the moment we met in the Zoom meetings, to the time we said Goodbye on that final day, we were as close as if we had known each other for years. There is a special connection amongst those who share a commonality, and we shared a love for Shakespeare, for Language Arts, and to see the passion in those around me for the same things that I did, I have no words. We just had a recent Zoom meeting, and it was as if we never left Utah. We shared ideas, we left our Chat Group open, and we are all still communicating like we did before. There are permanent connections that were made, and I feel as though we created our own little family. They have created a special place in my heart, and one that will always be filled. We read together, we ate together, drank together, and shared ideas together. We laughed, we cried, and will always have this connection. “I count myself in nothing else so happy / As in a soul remembering my good friends.” - Richard II Coming Soon... Coming Soon... "Those friends thou hast, and their adoption tried,

|

| After a catastrophic viral outbreak on a ship far, far away, eighteen-year-old Olivia Sindall (AKA "Vee") is sole commander of the Earth Vessel Aidan. Her only companion is the ship's namesake: her twin brother Aidan. But something is amiss about Aidan, making Vee extra willing to risk her life in answering a distress call from Terran beings on Barros 5. Of the 85 settlers under attack of the xenophobic, non-human Mazons, the siblings rescue and onboard 12 settlers. Romantic liaisons and jealousy ensue. Ultimately, the greenest envy comes from Aidan, who (spoiler alert!) turns out to be not Vee's flesh and blood, but a robotic replica of the same. Lanier differentiated between the strains of adaptation, all of which Blackman employs: in paraphrase, direct quotation (with enumerated page references, to boot!), naming, and what Lanier referred to as free plot adaptation. In Chasing the Stars, Shakespearean references commingle with references to Grease! and Dead Poets Society, sparking the question of which cultural artifacts shall persist over cosmic time. As Vee reminds us, "Good [art] is good, regardless of when or where it originated" (89). |

By articulating ties to Shakespeare and particularly Othello, Lanier showed how Shakespearean allusion supports, as opposed to drives, the narrative impulse. Instead of centralizing the story of the Black Moor in the Western world, Blackman's text interrogates the nature of jealousy beyond racial, ethnic, and even (post)human division. Perhaps Blackman might have capitalized on rich cultural gems outside of the Western world -- say the Ramayana, or Gilgamesh -- to drive home her point about origins. But to be sure, Vee's position as a woman of color, not to mention (more spoiler) her love interest's status as a drone, upends normative power structures in counter to the problematics of Othello.

More than that, though, Blackman's story deploys the known, vis-a-vis allusion, to make sense of the unknown. As Lanier explained, allusion "yokes disparate ideas to foster familiarity"; they are lighthouses marking the way as readers broach the transgressions of YA and speculative genres both. Anyone who has been young and in crazy love -- or has otherwise stepped outside of boundaries -- understands what I mean.

More than that, though, Blackman's story deploys the known, vis-a-vis allusion, to make sense of the unknown. As Lanier explained, allusion "yokes disparate ideas to foster familiarity"; they are lighthouses marking the way as readers broach the transgressions of YA and speculative genres both. Anyone who has been young and in crazy love -- or has otherwise stepped outside of boundaries -- understands what I mean.

Everybody’s a Critic: Analyzing Multiple Versions of a Scene

“It was MUURRRRDEERRRR!!”

I can still hear my former student’s eerie tone as he made his case during a final Hamlet discussion. That class was particularly caught up in the many unanswered questions of the play. Was Hamlet’s madness more than an act? Did he really love Ophelia? Why did Gertrude really marry Claudius? Why is Gertrude able to provide such a detailed description of Ophelia’s death? However, the question that often creates the most buzz among my students is this one: What does Gertrude know and when does she know it? I, too, love that question, so my interest piqued when Scott posed that exact question and said an upcoming lesson would allow us to explore it even further.

Scott brought five versions of the final Hamlet scene from five different directors (Cimolino, Branagh, Doran, Almereyda, and Gade) and asked us to watch how each version presented alternative answers to the Gertrude question. What did Gertrude really know and how much did she know before this scene began? Based on the film’s choices, what was the director trying to suggest about Gertrude’s role in Hamlet?

“It was MUURRRRDEERRRR!!”

I can still hear my former student’s eerie tone as he made his case during a final Hamlet discussion. That class was particularly caught up in the many unanswered questions of the play. Was Hamlet’s madness more than an act? Did he really love Ophelia? Why did Gertrude really marry Claudius? Why is Gertrude able to provide such a detailed description of Ophelia’s death? However, the question that often creates the most buzz among my students is this one: What does Gertrude know and when does she know it? I, too, love that question, so my interest piqued when Scott posed that exact question and said an upcoming lesson would allow us to explore it even further.

Scott brought five versions of the final Hamlet scene from five different directors (Cimolino, Branagh, Doran, Almereyda, and Gade) and asked us to watch how each version presented alternative answers to the Gertrude question. What did Gertrude really know and how much did she know before this scene began? Based on the film’s choices, what was the director trying to suggest about Gertrude’s role in Hamlet?

[Note from Scott--I use pictures of my dog Windsor to separate different clips in compilations. :) ]

Beyond monitoring Gertrude’s role in the scene, participants rotated through five critic roles, taking on a different critic specialty for each version and recording observations per these directions:

● Screenwriter: Closely follow the original text and note omissions, additions, pauses, stressed words, and rearrangements.

● Cinematographer: Note and describe camera movement and angles, lighting, etc. While it is not your official job, consider editing as well.

● Sound Editor: Listen for all music, background sounds, sound F/X, etc. Turn away from the screen to do this.

● Set and Costume Designer: Note and describe sets, costumes, props, etc., paying particular attention to colors, and symbols.

● Actor: Note and describe specific aspects of the performance, especially accents, subtext, and emphasis of certain words or lines.

When I use clips in class, I naturally lean in to the screenwriter and actor roles, focusing on which lines of a scene make the cut (or don’t) and how acting choices bring a specific interpretation of the text to life. However, giving attention to the other three roles helped us see just how much was going on in a specific clip to shape the interpretation. Even better, we weren’t overwhelmed by trying to individually observe just how much was going on in each clip. By distributing the critic roles, we could each narrow our focus, notice more details in a specific area, and have far more observations to share in our large group discussion. Depending on the version, Gertrude could be a clueless victim, a willing conspirator, or—as my former student argued—a calculating murderer.

A slam-dunk lesson staple has always been watching clips from different productions and comparing how the choices shape our understanding of a scene. Students are often surprised by the many possible takes on a character or setting. I usually ask students the following questions: What did you notice? What surprised you? Which version best matched your interpretation of the text? While those questions yield plenty of discussion points, asking future students to take on a specific critical specialty will generate more focused observations about the performance choices and provide a new way to explore that popular Gertrude question.

● Screenwriter: Closely follow the original text and note omissions, additions, pauses, stressed words, and rearrangements.

● Cinematographer: Note and describe camera movement and angles, lighting, etc. While it is not your official job, consider editing as well.

● Sound Editor: Listen for all music, background sounds, sound F/X, etc. Turn away from the screen to do this.

● Set and Costume Designer: Note and describe sets, costumes, props, etc., paying particular attention to colors, and symbols.

● Actor: Note and describe specific aspects of the performance, especially accents, subtext, and emphasis of certain words or lines.

When I use clips in class, I naturally lean in to the screenwriter and actor roles, focusing on which lines of a scene make the cut (or don’t) and how acting choices bring a specific interpretation of the text to life. However, giving attention to the other three roles helped us see just how much was going on in a specific clip to shape the interpretation. Even better, we weren’t overwhelmed by trying to individually observe just how much was going on in each clip. By distributing the critic roles, we could each narrow our focus, notice more details in a specific area, and have far more observations to share in our large group discussion. Depending on the version, Gertrude could be a clueless victim, a willing conspirator, or—as my former student argued—a calculating murderer.

A slam-dunk lesson staple has always been watching clips from different productions and comparing how the choices shape our understanding of a scene. Students are often surprised by the many possible takes on a character or setting. I usually ask students the following questions: What did you notice? What surprised you? Which version best matched your interpretation of the text? While those questions yield plenty of discussion points, asking future students to take on a specific critical specialty will generate more focused observations about the performance choices and provide a new way to explore that popular Gertrude question.

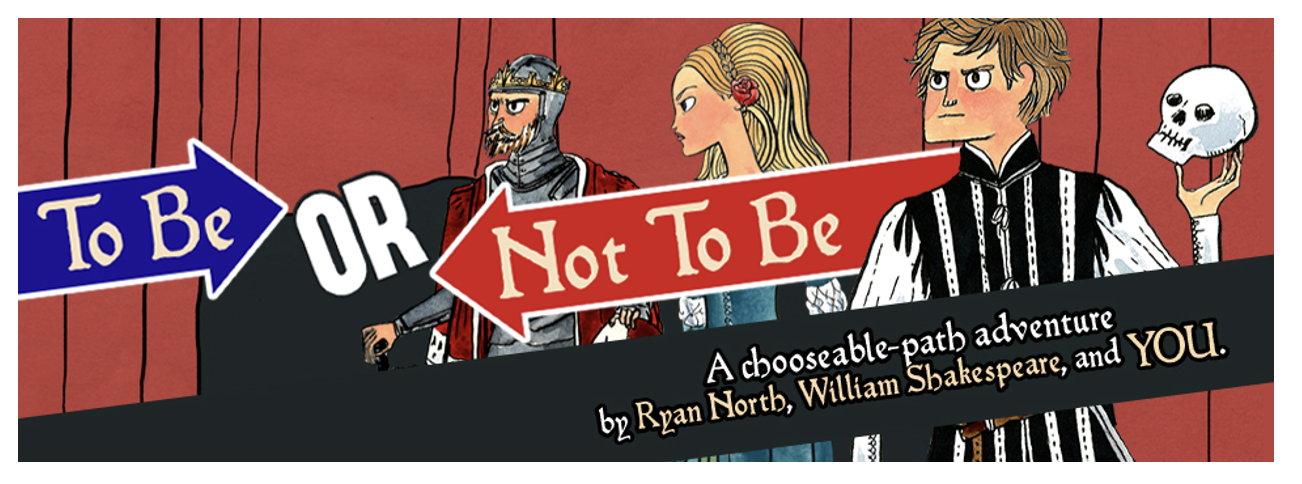

One of the reasons I hoped to be able to attend this institute was the idea of using video games to teach literature. I find it hard to tear my students, heck, even my own children, away from their video games, so I relished the idea of a “if you can’t beat ‘em, join ‘em,” approach. Let them learn while they play games? Sign me up! The fact that I am NOT a gamer did not hold me back.

Learning that I had been placed in the group that would demonstrate a lesson using video games based on Hamlet added to the feeling of serendipity. This is exactly what I was supposed to do! Then I got to looking at the games themselves. I found more questions than answers. Will this work with my school’s computers? How can I incorporate this into a lesson? Am I comfortable with assigning a homework assignment that states, “Make sure to play your game tonight?”

Since the lesson my group prepared is also closely tied to the session that Jenny presented, I got a bit more feedback from her than what was covered in the session. We discussed using YouTube video clips of people playing the game, having students work in groups on teachers’ computers, teachers playing while students observe and suggest moves, and many other options. I realized that video games based on literary works were something I could make work after all. I look forward to trying some in my classes this coming school year.

Learning that I had been placed in the group that would demonstrate a lesson using video games based on Hamlet added to the feeling of serendipity. This is exactly what I was supposed to do! Then I got to looking at the games themselves. I found more questions than answers. Will this work with my school’s computers? How can I incorporate this into a lesson? Am I comfortable with assigning a homework assignment that states, “Make sure to play your game tonight?”

Since the lesson my group prepared is also closely tied to the session that Jenny presented, I got a bit more feedback from her than what was covered in the session. We discussed using YouTube video clips of people playing the game, having students work in groups on teachers’ computers, teachers playing while students observe and suggest moves, and many other options. I realized that video games based on literary works were something I could make work after all. I look forward to trying some in my classes this coming school year.

At the climax of most slasher films, a scrappy group of survivors—typically led by the “final girl”—is faced with a decision: they can run out the front door and toward freedom or they can barricade themselves in a room on the second floor and hope the maniacal killer won’t find them; or, at the very least, the killer will be thwarted by a flimsy door and walk away from their murderous tour, knife low, with an “aw, shucks!” dampened by a tight-fitted hockey mask.

| Watching a slasher film, however, we know that the killer won’t be thwarted, won’t walk away from their murder spree by their own epiphanous volition, will get through the flimsy particle-board door, and will inevitably kill everyone except the one, virginal, tom-boyish female character who appropriates the killer’s overtly phallic murder tool—typically a larger-than-ever-practically-useful kitchen knife—before using that tool to kill the killer by penetrating his body in a way that would make Freud giggle gleefully from the grave. So, when we see a group turn to run up the stairs, we shift to the front of the couch and start pulling at our hair as we rock back and forth and scream at the television, lacking any agency to stop the tragedy that we know is coming. As Kim Hall contends in the introduction to American Moor (2020), “There is something unbearable about watching [something] with knowledge that could stop the tragedy unfolding in front of you” (i). And we do that again in parts two, three, and four, and for every remake, reboot, and reimagining. (This trope is so pervasive that is has been theorized, parodied, and subverted. It has even been used to sell car insurance.) |

I draw upon these slasher film tropes to illustrate a major issue w/r/t dynamic texts that have been reduced to banal, read-along and watch-along, experiences in classrooms across the world wherein all individual character and audience agency has been removed. Reading along or even watching along, we’re always passive observers in a story bound for the second-floor flimsy door. And, eventually, that hair pulling and that nervous rocking disappears behind a jaded curtain. The films get old, and we stop enjoying them in real time, only looking back when nostalgia dictates or when an edgy art-house director helms the newest installment of the horror series that subverts gender roles, deconstructs racial structures, and elevates marginalized voices.

And they promise new takes on the old classics but hit the same notes.

And even with those bold, progressive choices, we still arrive at the bottom of a staircase.

And they promise new takes on the old classics but hit the same notes.

And even with those bold, progressive choices, we still arrive at the bottom of a staircase.

| And after the death, we leave the theater or theatre wondering the different ways in which the stories could have been different: how everyone could survive the night, how Prince Hamlet and Ophelia could have grown old sitting side-by-side in the throne room of Elsinore as their children played at their feet, how Romeo and Juliet could walk proudly through the farmer’s market in a peaceful Verona, and how Tamora could go on for another five minutes in life not knowing that she ate her own children. |

By way of a long digression, we finally come to the question that started Jenny’s slide deck: “What can games teach us?” Or, restated in the context of our class-discussion, “How might we use the agency and choices that certain games provide to open new-and-exciting experience, understandings, and thoughtful critiques of Shakespeare’s very old, hermeneutically-picked-bone-dry plays?”

Together, we explored games which situate the student-player in the world of Shakespeare’s Hamlet as active participants rather than as passive observers. For example, in To Be or Not to Be (2015) players explore Shakespeare’s Hamlet in “the way it was meant to be experienced: In a non-deterministic narrative structure where you end up thinking maybe you made a wrong decision.” The game allows student-players to “explore other options” and “go on a different adventure” each time you revisit the story. Situated around moments of choice in the play, To Be or Not to Be allows the student-players to (almost) fully immerse themselves in the plot of the text by providing real-world (as it pertains to the world of the story) consequences for each decision.

In a way the consequences of our choices seem wholly disconnected from the texts as it was meant “to be” (ba-dum-tss!) but in the exploration of those choices in the text that were “not to be” (I’ll be here all week, folks!), the consequences and new storylines defamiliarize the text and allow the student-player the necessary critical distance from the play to see the importance of those individual moments. Given that critical distance, the player can more fully critique the form or structure of the play, itself. Tired plot points become teachable moments in a fresh way.

So, the question became: “How might we use these adaptations in an authentic and equitable way?” Or, phrased differently: “How can we introduce videogames in a manner that isn’t cheesy for our students and so all students can play?”

The accessibility of the game was a major concern in the discussion. After all, district budgetary constraints will dictate the ability of our students to play games on school devices. Moreover, personal budgetary constraints might limit their ability to play these games at home. Even within this class, some of us were unable to play To Be or Not to Be due to incompatible operating systems.

Luckily, To Be or Not to Be is available in book form, so students might get the same experience without technology. Another avenue of access might be utilizing Twitch TV or YouTube streams. Introducing Twitch and YouTube brings familiar technologies and experiences into the classroom as a means for students to engage with complex texts. Likewise, these technologies level (in some regard) the issues of equal access—most of us experienced the text through play-through videos.

In a way the consequences of our choices seem wholly disconnected from the texts as it was meant “to be” (ba-dum-tss!) but in the exploration of those choices in the text that were “not to be” (I’ll be here all week, folks!), the consequences and new storylines defamiliarize the text and allow the student-player the necessary critical distance from the play to see the importance of those individual moments. Given that critical distance, the player can more fully critique the form or structure of the play, itself. Tired plot points become teachable moments in a fresh way.

So, the question became: “How might we use these adaptations in an authentic and equitable way?” Or, phrased differently: “How can we introduce videogames in a manner that isn’t cheesy for our students and so all students can play?”

The accessibility of the game was a major concern in the discussion. After all, district budgetary constraints will dictate the ability of our students to play games on school devices. Moreover, personal budgetary constraints might limit their ability to play these games at home. Even within this class, some of us were unable to play To Be or Not to Be due to incompatible operating systems.

Luckily, To Be or Not to Be is available in book form, so students might get the same experience without technology. Another avenue of access might be utilizing Twitch TV or YouTube streams. Introducing Twitch and YouTube brings familiar technologies and experiences into the classroom as a means for students to engage with complex texts. Likewise, these technologies level (in some regard) the issues of equal access—most of us experienced the text through play-through videos.

I leave this discussion thinking of how I can introduce games into my discussions of Shakespeare’s plays in class, thinking of ways to have my students experience the play, experience the decisions each character makes and the consequences of those decisions.

Perhaps, as they reach the bottom of the stairs with a killer at their heels and choose, instead, through an analysis of the consequences, to run out the door to safety, my students will be better equipped to realize why running up the stairs was such a horrible idea in the first place.

Perhaps, as they reach the bottom of the stairs with a killer at their heels and choose, instead, through an analysis of the consequences, to run out the door to safety, my students will be better equipped to realize why running up the stairs was such a horrible idea in the first place.

Author

25 teachers gathered in Ogden, Utah to work together and learn about Shakespeare and Adaptation from three regular and several visiting faculty. These are their stories.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed